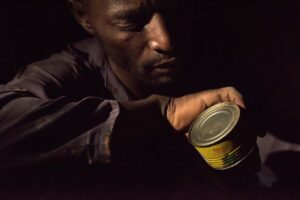

Robert, an ironmonger in Kiteezi, Kampala, makes small kerosene lamps out of tin cans for a living. He searches in the landfills of Kampala for steel tins which he takes and cleans up, carefully checking them for rust.

He uses steel because it can be recycled over and over again indefinitely, with no loss of its essential properties. Once he finds a good can, Robert makes a lid for it from pieces of another can and then carefully inserts a cotton wick through an opening he makes in the new lid. Then he adds a small handle to make the lamp complete. When filled with kerosene these little lamps, known in Luganda as tadooba, provide a steady, though smokey, source of light. Once Robert has a batch ready he goes out on the city streets in search of buyers. His lamps are used by street vendors to light their stalls and in informal housing where electricity is scarce. The kinds of upcycling done by makers like Robert forms the basis of a micro-economy for people living around Kampala’s major landfill sites. It allows them to earn a living while helping to reduce waste and protect the environment.

Uganda, located in East Africa, has been known for its controversial stance on LGBTQ rights, with laws that have garnered significant international attention and criticism. Uganda’s legal framework pertaining to LGBTQ individuals has always been harsh and oppressive. The Anti- Homosexuality Act, colloquially known as the “Kill the Gays” bill, was introduced in 2009 and later passed into law in 2014. While the Act was invalidated by the Constitutional Court in 2014, homosexuality remained criminalized under the colonial-era law that punishes ” carnal knowledge against the order of nature”

In 2023, Uganda’s parliament has passed a mostly unchanged version of one of the anti-LGBTQ+ bill. Despite four amendments, the bill retains most of the measures of the legislation.

Those include the death penalty for certain same-sex acts and a 20-year sentence for “promoting” homosexuality, which activists say could criminalize any advocacy for the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer citizens. A measure that obliged people to report homosexual activity was amended to only require reporting when a child is involved. Failure to do so is subject to five years in jail or a fine of 10 million Ugandan shillings (£2,150). Anyone who “knowingly allows their premises to be used for acts of homosexuality” faces seven years in jail. In addition to legal repercussions, the LGBTQ community continues to face widespread discrimination, social stigma, harassment and violence, often perpetrated by both the state and non-state actors. NGOs and international human rights organizations have been actively advocating for the protection of LGBTQ rights in Uganda, although progress has been slow, and challenges persist in changing public attitudes and dismantling discriminatory laws.

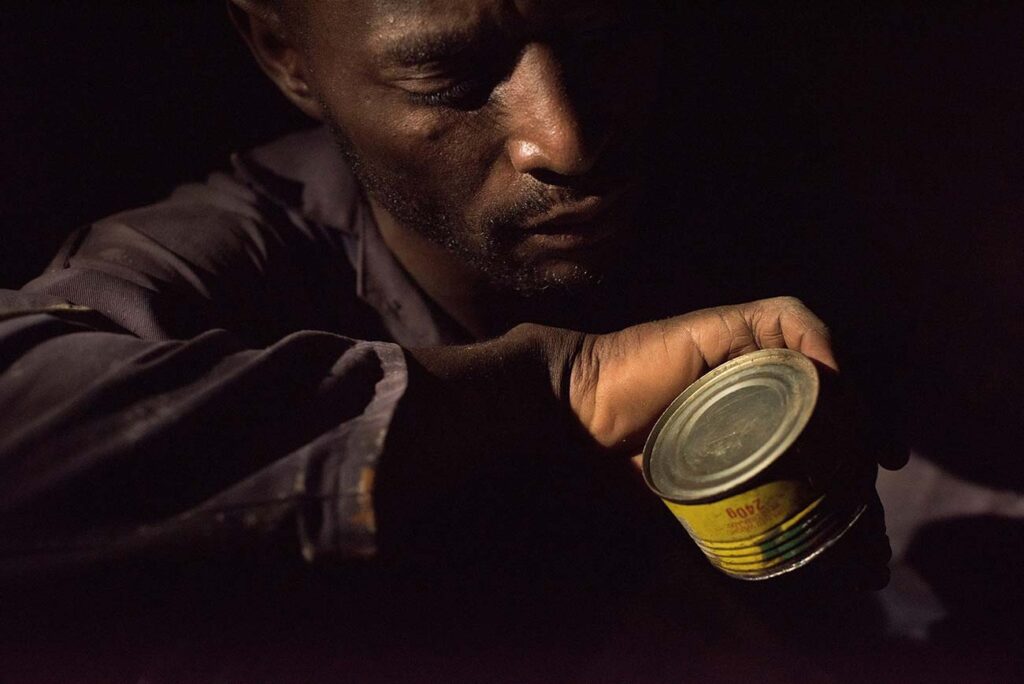

“Where love leads to death” aims to provide viewers with an intimate glimpse into the lives of LGBTQ individuals in Uganda, emphasizing their determination to live authentically despite the threat of prosecution and discrimination. Individuals of the community have been forced to relocate to new homesteads to protect their identities and safety leaving behind familiar surroundings and building new lives in an attempt to find acceptance and security, The bittersweet emotions! They live concealed in the shadows, adopting strategies to avoid being seen by neighbors who may pose a threat to their safety. Their faces obscured, they wear masks of anonymity, struggling to conceal their true selves from a judgmental society. They hide their pro-LGBTQ outfits beneath layers of clothing concealed out of necessity. An underscore to the importance of self-expression and the lengths to which individuals must go to protect their personal freedom and safety in an environment hostile to their existence.

Members of the LGBTQ community gather in shelters, sanctuaries where they can seek solace and find support amidst a society that rejects them. This highlights the resilience and strength found in collective spaces, where individuals find strength through community bonds and shared experiences. This Photo story serves as a testament to the enduring spirit of LGBTQ individuals who refuse to be silenced or erased.

Story by Andrew Kartende

In most African countries, unemployment and underemployment have continued to rise, and the problem is exacerbated by a large young population, weak national labour markets and persistent poverty. Youth unemployment in Uganda is one of the highest in Africa. Uganda also has the second largest percentage of young people in the whole world.

According to Action Aid, in 2012 six in every 10 Ugandans were unemployed. Many lack the skills employers need, but the core problem is that the economy is not expanding as fast as the labour force.

This situation forces citizens to seek new opportunities, surrendering themselves to labour exporters who range from legitimate businesses all the way to traffickers. These companies send workers to Middle-Eastern and Asian countries where they are all too often subjected to inhumane conditions, and when they return home it is hard for them to get back into the formal job market so their savings, if they have any, are quickly used up. Soon they end up where they started, struggling to earn a decent living. Since the informal sector in Uganda has always been a major source of employment for the population, many of them pick it up from there.

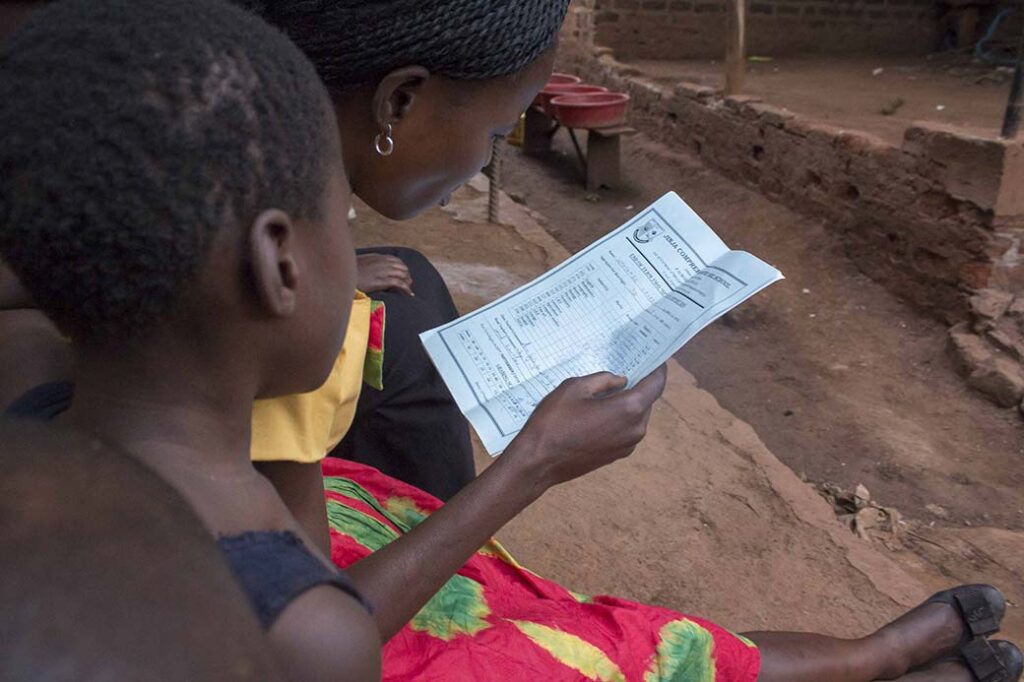

Annet Balondemu Rachel is a 33 year old single mother of three. She worked in the Sultanate of Oman as a domestic worker until she was deported after complaining of being physically abused. She was unable to seek justice as Oman’s labour law excludes domestic workers from its protections, so those who flee abuse have little avenue for redress. “I can’t talk about it. What happened in Oman was not good at all”, she tells me. Trying to get back on her feet, she has immersed herself in a range of jobs to try to make ends meet.

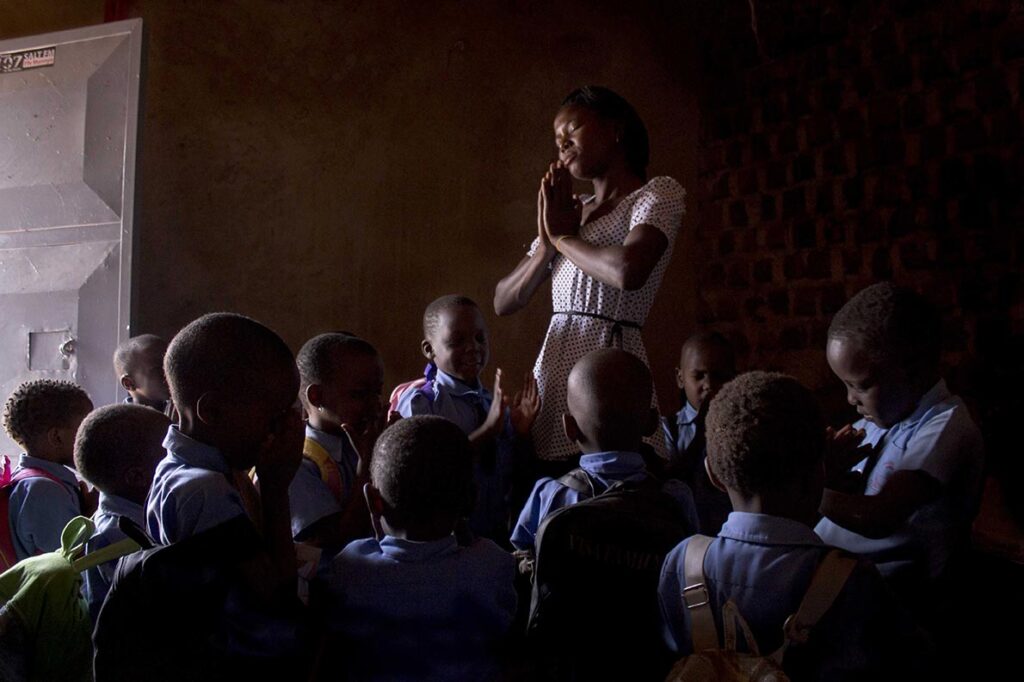

She works as a street vendor, a nursery school teacher and a church leader, rushing between workplaces throughout the day in an endless rhythm, with often only a change of shoes to mark the new role. She is passionate about teaching, and is employed at an informal nursery school for half of each day before collecting her stock and walking to the nearby

trading centre where she sets up a small stall with toiletries and sweets for pedestrians walking by. At the end of the week she is part of a community church, where she leads the congregation in prayer.

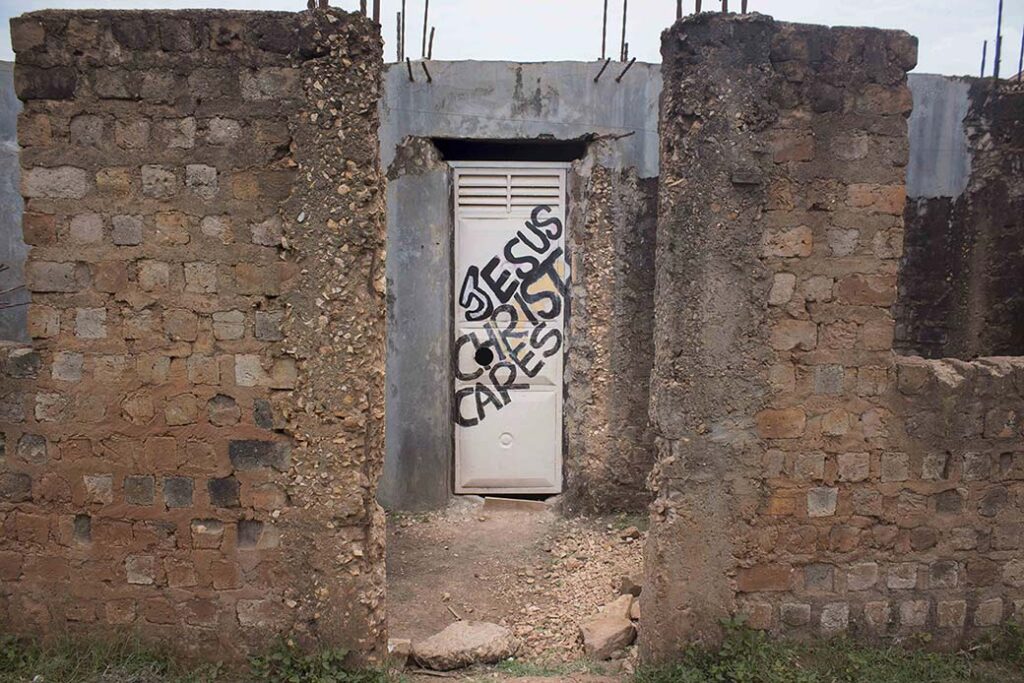

She takes most of her earnings back home to Jinja, some 80 kilometres from Kampala, where her children stay with their grandmother. She tries to go as often as possible to check up on her children’s school progress, but the visits are always too brief as she rushes back to the city and to her many jobs. She and many like her inhabit a world that hides in plain sight, full of familiar gestures but temporary and always uncertain. Roadsides become workplaces, empty plots sprout churches and half-built buildings house schools as a generation fights not to be swept away by the pace of progress.

By Andrew kartende